ASVOFF, A Shaded View on Fashion Film, the fashion film festival, founded by Diane Pernet will take place in Paris from December 1st to December 3rd 2021. For this 13th edition the president of the jury is Canadian filmmaker Bruce LaBruce. At this occasion he also presents his latest film Saint Narcisse (2021). The perfect opportunity to come back to his work marked by his reflections, both political and cinematographic.

G.Wen: We see in you the new Jean Genet, but who is Bruce LaBruce?

BLB: I don’t think anyone considers me the new Jean Genet.

G.Wen: I must of read this in some other magazines

BLB: Really? That’s a lot to live up to… I’m more like the new Don Knotts, an American comedian, film star in the 60s and 70s… A kind of nerd… I’m just a filmmaker, that’s all. I just make films. You know when they asked John Ford what he did, he said: “I’m John Ford, I make westerns.”

G.Wen: You make westerns? LOL

BLB: Maybe I will make a western, that’s an idea, a zombie western…

G.Wen: In your films, what is the part of the Bruce LaBruce’s identity?

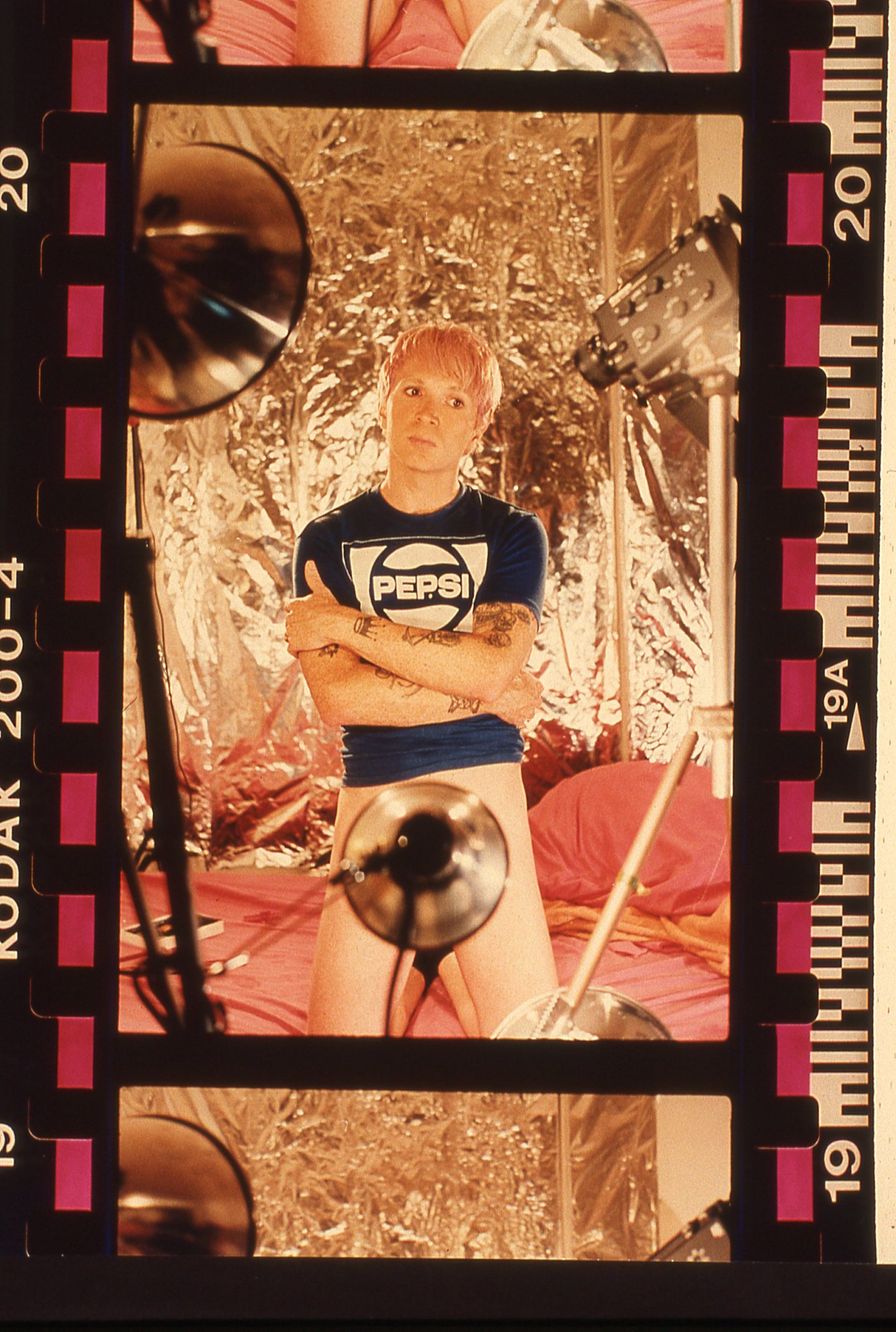

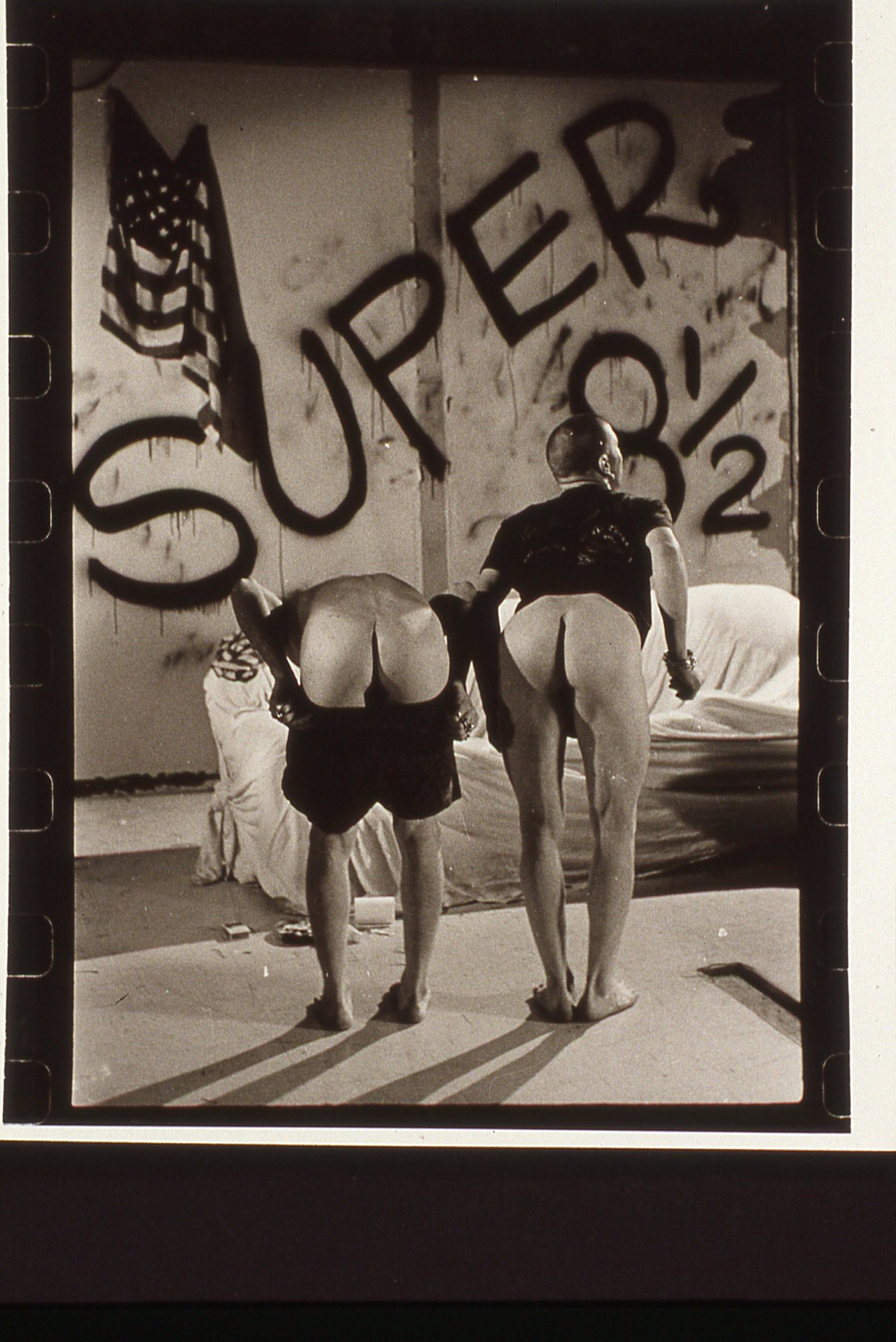

BLB: I appeared as an actor in my early short experimental movies in the 80s and then in my first three feature films: No Skin Off My Ass, Super 8 1/2 and Hustler White, which are the subject of a DVD set, the Tender Life, and a documentary about me made by Angélique Boslo.

The character in each of those three films is somewhat different, but each one is an aspect of my personality. In No Skin Off My Ass, I play a very romantic, dreamy hairdresser. He’s effeminate, but not to much, he’s a lonely kind of romantic homosexual who happens to fall in love with a skinhead. In Super 8 1/2, I play a washed-up porn star. He’s very angry, violent, aggressively gay, and a sort of pseudo-intellectual. When I made No Skin Off My Ass, I had a scene where I had sex with my boyfriend, I never expected to be shown outside Toronto. From some kind of basement punk bar, alternative art space, it got picked up by the film festivals, so suddenly it was showing all over the world , it became a cult film. These very naive scenes of me making porn, having sex in front of a camera were everywhere. It kind of tripped me out, so Super 8 1/2 is about that experience, that’s why I play a washed-up porn star who has a nervous breakdown. Because I almost had a nervous breakdown in real life. So, there’s definitely autobiographical aspects. And then, in Hustler White, again I play that kind of filmmaker who’s researching a film about male prostitutes, hustlers in Santa Monica Boulevard and L.A. So, I went to L.A. for a year and made a film. That was my escape from Toronto. Again, I play this kind of imperious kind of intellectual queen. It all goes back to my studies. I initially went to college to become a film critic, and ended up doing a master’s degree in cinema, cinema theory, and social and political theory. That’s where all these characters come from, those intellectuals or pseudo-intellectuals. It’s also a bit of Kenneth Anger ‘s Hollywood Babylon.

G.Wen: You took another name. What meaning you bring with it?

BLB: It’s funny you should ask that…I created this Bruce LaBruce character to star in my films. It was, in a way, an exaggerated version of myself: more equeenye, more imperious, tougher also, fighting kind of queer character, very bitchy, some people would be afraid of. Also playing this character in real life: for example, when I presented the films, I used some of these aspects. Again, I was exaggerating aspects of myself. It made me a little schizophrenic. I had my real name that only a few relatives used to refer to me, and then I had this character that I had created for myself. It was becoming a strange schizophrenic identity, which ended up leading to the Super 8 1/2 depression. And then, I learnt how to integrate them together. Funny because now Facebook finally caught up with me: they told me I had to use my real name on Facebook. I do so much business on Facebook and have so many contacts… I have to use my real name now, it has LaBruce in brackets. But it really made me angry because it’s the name people call me in daily life, they call me Bruce LaBruce. That’s who I am, the name I go by, everyone knows me by that. And yet I have to give them this very private name that only my really old friends and family use. So, it made me really angry and I felt really exposed.

G.Wen: What place do body and sex take in your work?

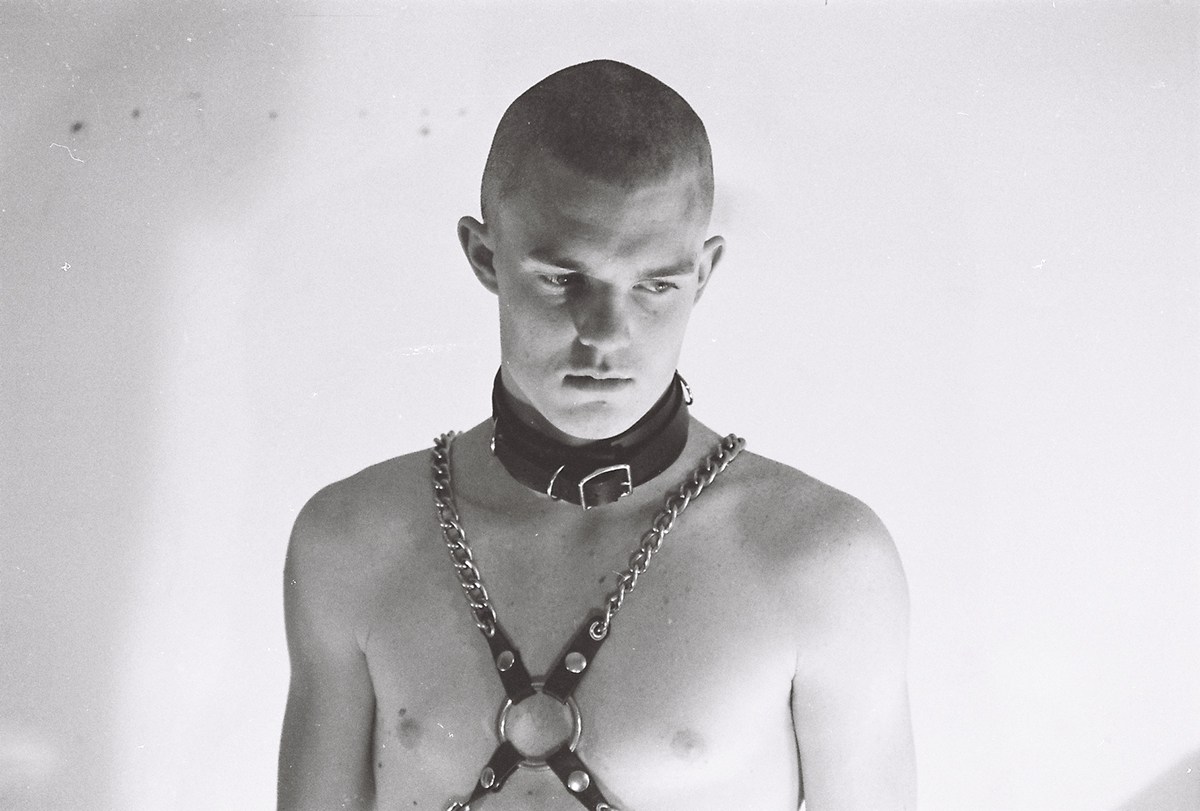

BLB: Well, some people have said that it’s very post-body, post-sex, post-human. Because the body is, in my films, quite often ravaged, tortured, bloody, it’s kind of disposed of, but the sexuality still comes out of that, the sexuality is part of that, the violent body. [I guess it’s a response…] I came out of the generation of the 80s gay liberation, where sex was very strong, a time of sexual militancy, and it was not only about being unapologetic or about being homosexual, but also about being aggressively sexual, experimental, fucking a lot, trying all different kinds of sex. Fetishism was part of the whole gay world. So, I’ve always maintained that attitude towards sex, using it also politically to really throw gay sex into people’s face, into the faces of the straight world, as a kind of reaction towards this liberal tolerance, where liberals say: “oh yeah, it’s OK to be gay as long as you don’t put it in my face, as long as you don’t go too far, too extreme.” So, it was like “I’m going to do it the way I want to do it and if you don’t like it, you can fuck off…”

In my zombie movies, the identity with the body becomes very fluid. It’s not about the orifices, it’s not about just the mouth and the ass, it’s also about penetrating the body itself, in the head or in the stomach, in the heart. I’ve always been ambivalent about homosexuality, like identity politics, having a gay identity and behaving agreed to the rules of how you’re supposed to act as a gay person… So, it’s a bit the same thing, like using the imagination to think of the body and the limitations it’s supposed to have, making it something more organic, more polymorphic perverse, more like total Gestalt of the body.

G.Wen: You play with genre cinema…

BLB: One thing I like to do in my work is to juxtapose unexpected genres, two or three different genres together that you wouldn’t expect. When I made L.A. Zombies, for example, it’s a hardcore porn movie, it’s a horror movie, it’s a gore movie, but it’s also about a homeless schizophrenic, so it has almost a fresque, documenting all these people in L.A.. Or when I made my film The Raspberry Reich, it’s an agit-prop film, a propaganda film, it’s a kind of investigation of the radical left, or a satyre of the radical left, but it’s also a porn movie, and a comedy… So, I like putting unexpected genres together, especially introducing an element of romance to porn, because everyone expects porn to be hard, and with no sense of humour. In the 70s, you would find more narrative porn, more humour, actual characters and more intricate narrative plots. You don’t see that anymore. That’s the thing in porn that really interests me because you’re not just showing the sex act, you’re interpreting sexuality, you’re putting sexuality in a socio-political context, as well as showing it blunt. So, I think porn can be much more than just what people expect it to be, and especially it’s a great political propaganda tool if you use it correctly because, everyone watches porn, and it’s something people almost watch unconsciously. If you put a political message in it, it can really disseminate and get into people’s unconscious.

G.Wen: In No Skin Off My Ass, you investigate about the neonazi skinheads’ inability to accept homosexuality.

BLB: I made two films about neonazi skinheads, No Skin Off My Ass and Skin Flick (its hardcore version: Skin Gang) It’s a kind of an investigation of these working-class characters who not regard themselves as gay. It’s about identity politics. They’re having homosexual sex, but they have no relation to gay identity. Which is a fil rouge to all my films. No Skin Off My Ass is romantic and naive because the hairdresser thinks he can reform the skinhead. At first, he says: « I don’t care about your political beliefs, it’s more about style and sexual attraction », but the sister of the skinhead is humiliating him for being a neonazi and saying: «you’re an ass, you’re an idiot, why don’t you become a punk and be politically a leftist, not an extreme right-wing?». And ultimately, between the hairdresser and the sister, they finally reform him and he becomes a nice punk at the end. It’s a politically naive message.

Skin Flick, it’s somber and complexe, because is investigating the historical relationship between fascism and homosexuality. Legendary, as we go back to the SA, the secret police, in the Third Reich, with Erich Rohm, Visconti shoed in Les Damnés. But a lot of extreme-right wing leaders historically have been gay like Michael Kühnen. I have a new experimental film titled Ulrike’s Brain, which is partly about Michael Kühnen who was one of the main leaders of the neonazi right in the 80s. He was openly gay and died of AIDS in 1989. He took up that tradition of fascist homosexuality. Or Mishima, who was in this idea of homoerotic bonding between men. And in Skin Flick, the skinheads are critiqued at a certain level, but they’re also compared to the bourgeois gay couple. And in some ways, the skinheads are, not more sympathetic, but some aspects are appreciated, like their working-class simplicity, their loyalty to one another and their homoerotic bonding and the fact that they’re not bound by sexual identity politics. And the bourgeois mixed-race couple are being critiqued for being shallow and superficial, they’re not honest with each other and their relationship, their bourgeoisness is critiqued. There’s retribution against the skinheads because they’re torturing these guys. It is a very complicated depiction of homosexuality.

G.Wen: What is your film, The Misandrists, about?

BLB: The Misandrists is about a group of lesbian separatist essentialist feminist terrorists, whose strategy of radical revolution is making lesbian porn and forcing people to watch it. It’s kind of a B-movie, it’s low budget, but it’s also referencing low-budget B-movies, soft-porn 70s movies. Again, it’s a loose sequel to The Raspberry Reich, which was an affectionate critique of the radical left. It kind of supported the politics of the radical left but at the same time is a critique of people who don’t practice what they preach, who contradict themselves, intellectually or politically. I do the same with feminism, the second wave of feminism, in The Misandrists. So, it’s a critique and I would call it a feminist film.

G.Wen: Do you see your work as an intellectual fanzine?

BLB: Yes, I started out making fanzines and, in a way, my films are like moving fanzines. Especially my early super-8 experimental films have the same aesthetic of collage and juxtaposing images from the punks, mixed with hardcore gay pornography. Just to be provocative because a lot of punks in the 80s were homophobic. So, it was really to row them up and make them angry. And my films tend to be super-referential, with a lot of links to different genres, different Hollywood movies, different European art movies. My films are often remakes of other movies. So, The Misandrists, for example, is a remake of this Don Siegel film with Clint Eastwood and Geraldine Page, The Beguiled. There are also elements borrowed from the Dirty Twelve, and I’m referencing the soft-core 70s porn films like Bilitis and Histoire d’O. So, it’s taking stuff from all over and stealing it, it’s like bricolage, putting unexpected connections together.

G.Wen: Can you tell me about Saint Narcisse? Is there a duality being addressed? The Double close to a Dostojevski sprinkled with genre film culture? is it also a second Quebec production with Gerontophilia? What is the irreverent dimension of the film?

BLB: I’ve always had a fascination for twins. When I lived with my best friend during my university years, I hung out with her and her twin sister and observed their uncanny psychic connection. More recently, narcissism has obviously become the default psychological state, the ideological white noise, of the new millennium, evidenced by selfie culture and social media solipsism. So I thought it was high time for a more contemporary reinterpretation of the Narcissus myth.

Saint-Narcisse is an amalgam of references to classical mythology, organised religion, and the lives of witches and saints. But I was mostly interested in the way these myths have been interpreted historically in cinema. I was thinking of Cocteau’s contemporary interpretation of the Orpheus myth, for example, or Derek Jarman’s supremely gay interpretation of Saint Sebastian, or the way that lesbians are often coded as witches in mainstream movies. My representation of Catholicism is largely based on the way it has been interpreted in movies, from Pasolini’s “Salo” to Russell’s “The Devils.” In other words, my interpretation of mythology is based on how I see it in my imagination based on cinematic influences.

There are a number of dualities in the film: city/country, Wiccan/Christian, male/female, gay/lesbian, mother/father, English/French. The world of Beatrice, the Earth Mother – the house in the woods, nature, witchcraft, DIY art, smoking weed, Sapphic desires – is set in contrast to Father Andrew’s world – the monastery, artifice, the mystical lives of Saints, classical art, chemical drugs, gay male desire. There are two sets of twins in the film – Dominic and Daniel, the literal twins, and Agathe and Irene, the identical mother and daughter, both of whom are the object of Beatrice’s desire. The film is ambivalent about these dualities, celebrating and critiquing aspects of both, and ultimately suggesting that in some ways they are two sides of the same coin (coins featuring prominently in the narrative – the coin Dominic gives back to Beatrice paralleled to the coin of Saint Sebastian that Father Andrew has given to Daniel to wear around his neck). If there is a piece missing in the film, perhaps it is the notion of morality. The film doesn’t pass judgment on the characters and their contravention of conventional morality as explore its potentialities.

This is the second feature film I’ve made in Quebec – the first being “Gerontophilia” (2013) – with support from Quebec government film financing agencies, SODEC and Quebec Telefilm. There was also financial support this time from the CBC, Canada’s public broadcaster. I’ve always had a strong appreciation for Quebecois cinema since I was a kid. In fact, both “Gerontophilia” and “Saint-Narcisse” are homages, in a sense, to films made in Quebec in the lates sixties and early seventies such as Jutra’s “Kamouraska” and Paul Almond’s great trilogy of “Isabel,” “The Act of the Heart,” and “Journey” starring his then-wife Genevieve Bujold. Because of the “two solitudes” mentality inherent in the Canadian psyche – the Anglo majority versus the Franco minority – Quebec has developed a very distinct culture and cinema that is arguably more political and more aesthetically rigorous, evincing perhaps a more European-influenced sensibility. So I love working with Quebec casts and crews that regard cinema as so essential to their cultural experience.

G.Wen: Do you see your work as an intellectual fanzine?

BLB: Yes, I started out making fanzines and, in a way, my films are like moving fanzines. Especially my early super-8 experimental films have the same aesthetic of collage and juxtaposing images from the punks, mixed with hardcore gay pornography. Just to be provocative because a lot of punks in the 80s were homophobic. So, it was really to row them up and make them angry. And my films tend to be super-referential, with a lot of links to different genres, different Hollywood movies, different European art movies. My films are often remakes of other movies. So, The Misandrists, for example, is a remake of this Don Siegel film with Clint Eastwood and Geraldine Page, The Beguiled. There are also elements borrowed from the Dirty Twelve, and I’m referencing the soft-core 70s porn films like Bilitis and Histoire d’O. So, it’s taking stuff from all over and stealing it, it’s like bricolage, putting unexpected connections together.

G.Wen: Tell me about 24 h in Bruce LaBruce’s life

BLB: I won’t describe the last 24 hours… Well, it depends on where I am. If I am at home in Toronto, I’m married, I have a husband, so we’re very domestic. I just get up and have breakfast and do yoga, work, write, and binge TV, and then sleep. And I do domestic things with my husband, like shopping and cooking. But if I’m traveling, which I do half the time, then it’s very unpredictable. But too much partying, too many interviews… I usually make films not in Toronto, but in other cities. I made Gerontophilia in Montreal recently, I made four films in Berlin, two in L.A. I’m probably working 24 hours a day on a film or partying and promoting. And DJing.

G.Wen

all images courtesy of Bruce LaBruce