by Alexandra I. Mas

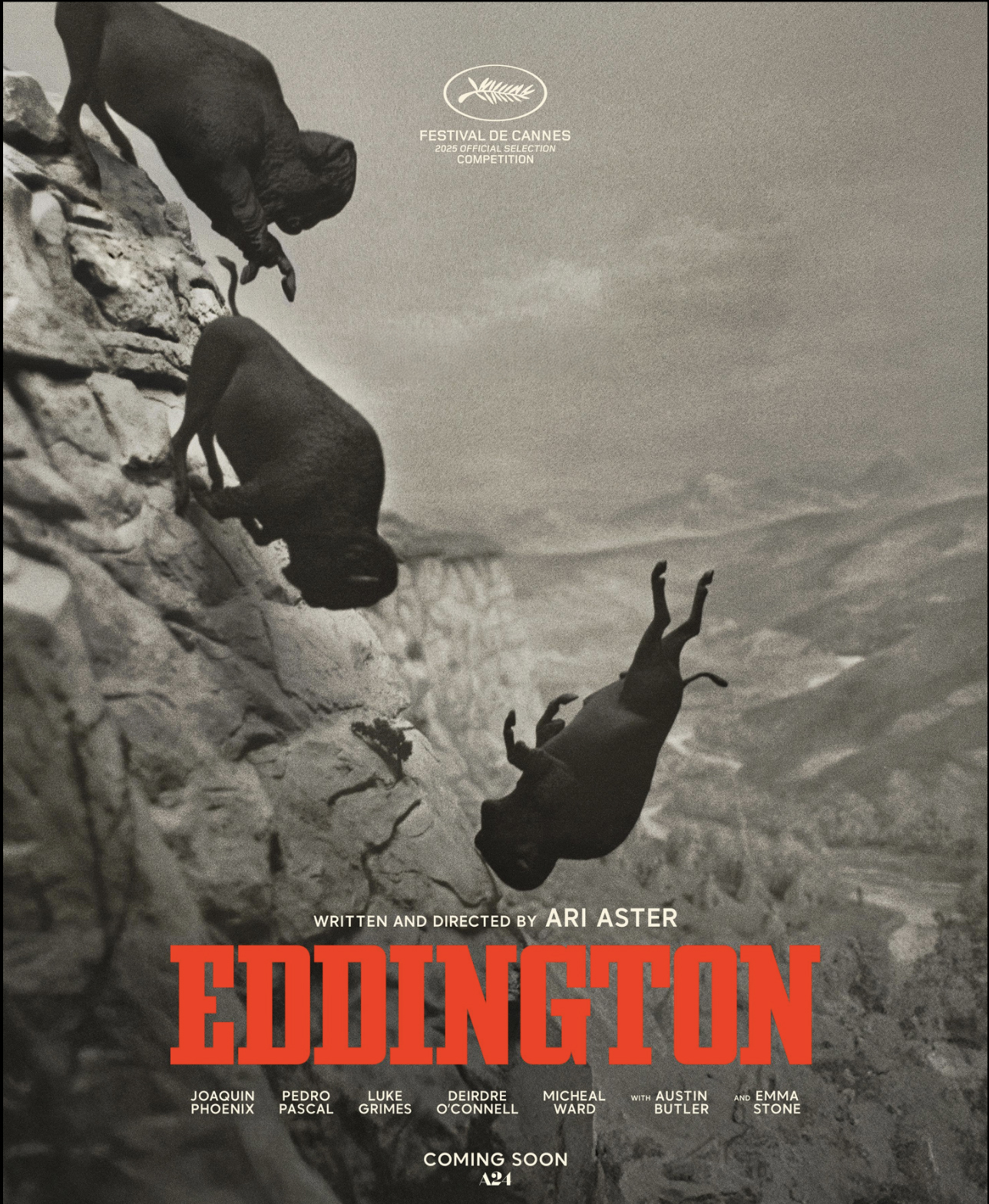

It feels like a group of friends gathered around a table and decided, half-laughing, half-terrified, to make something about the direction our crumbling society is headed. The film’s billboard itself feels like a scream — pointed, too obvious to be ironic, too ironic to be ignored.

So take everything that is grotesque, everything absurd, criminal, manipulative, and hollow — and there you have Eddington. This forgotten patch of nowhere, somewhere in the depths of America, becomes a mirror of our entire culture: swollen with fake news, paralyzed by performative morality, rotting under the weight of nostalgia, and buzzing with weaponized nonsense.

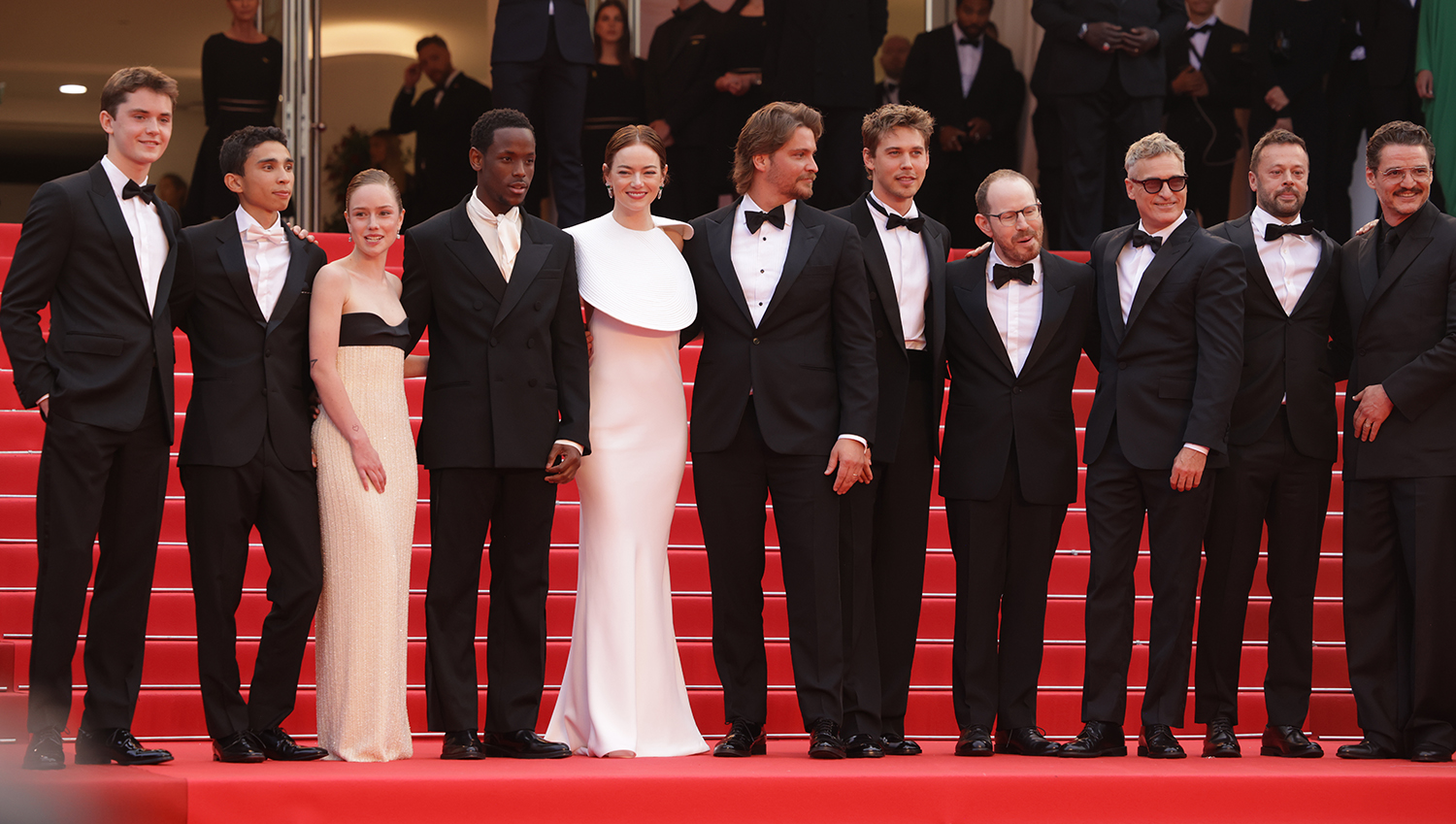

Here, Ari Aster builds the pastiche of a nation collapsing under its own illusions, where community is replaced by suspicion, where collective delusion blooms like a weed, and where patriotism is little more than a costume for despair. In this madness, Joaquin Phoenix stands as the sheriff: grumbling, confused, derailed. A man no longer trusted, not even by himself. He lumbers through a fog of conspiracy, marital fatigue, and quiet paranoia, carrying the burden of a role that has lost all meaning. Not quite a hero, not yet a villain, just a man slowly sinking into his own story.

Facing him, Pedro Pascal plays the town’s mayor with a kind of composed futility, charming, well-dressed, and utterly ineffective. A bystander in a world on fire. And then there is Emma Stone, magnetic, otherworldly, quietly unhinged. As the sheriff’s wife, she stitches her inner chaos into porcelain dolls and suburban rituals. Her performance is a séance of inherited madness: soft-spoken, meticulous, deeply disturbing. She doesn’t scream; she simmers. She isn’t merely acting — she’s haunting.

Surrounding them is an ensemble drawn with eerie precision: Deirdre O’Connell, Clifton Collins Jr., Michael Ward, Luke Grimes, each trapped in their own psychic echo chambers. Every character is a glitch in the simulation, every line a thread unraveling. If you crave absurdity wrapped in sincerity, satire soaked in dread, this is your feast.

Aster doesn’t lean into the surreal, he lets it seep in, quietly. The COVID-19 lockdown provides the backdrop, but it’s more than a timestamp: it’s a pressure cooker. The fear, the boredom, the slow decay of reality itself, it’s all here. Misinformation spreads like smoke, neighbors turn on each other, and every conversation carries the weight of make-believe truth.

Darius Khondji’s cinematography captures it with clinical grace — each shot pristine, composed, trembling. The classic geometry of westerns is stripped of nostalgia, exposing only emptiness. This simplicity propels the film down a slope of dark farce and bitter clarity. Light floods everything, but it reveals nothing. The sheriff’s office hums like a church abandoned mid-sermon. The streets are too quiet. The silence is not peace, it’s a prelude to the loud, false manifestations that mimic the headlines.

The camera floats, uncommitted, suspicious. It offers neither comfort nor answers. It hovers just close enough to witness, but always distant enough to escape blame — just like our characters. What emerges is not a plot, but an autopsy: of belief, of identity, of any shared notion of truth.

Eddington is not a satire with punchlines. It’s a mourning song, slow, uncomfortable, and far too familiar. No redemption, no savior on horseback, because the savior has already been massacred and repurposed into a pantin. The epilogue is clear: our disintegrating society won’t collapse with a bang, but in soft, polite conversations gone horribly wrong. And in that, Aster delivers a chilling reminder: it could always go even more wrong.