BI GAN and the Aesthetic Megalomania

by Alexandra I. Mas

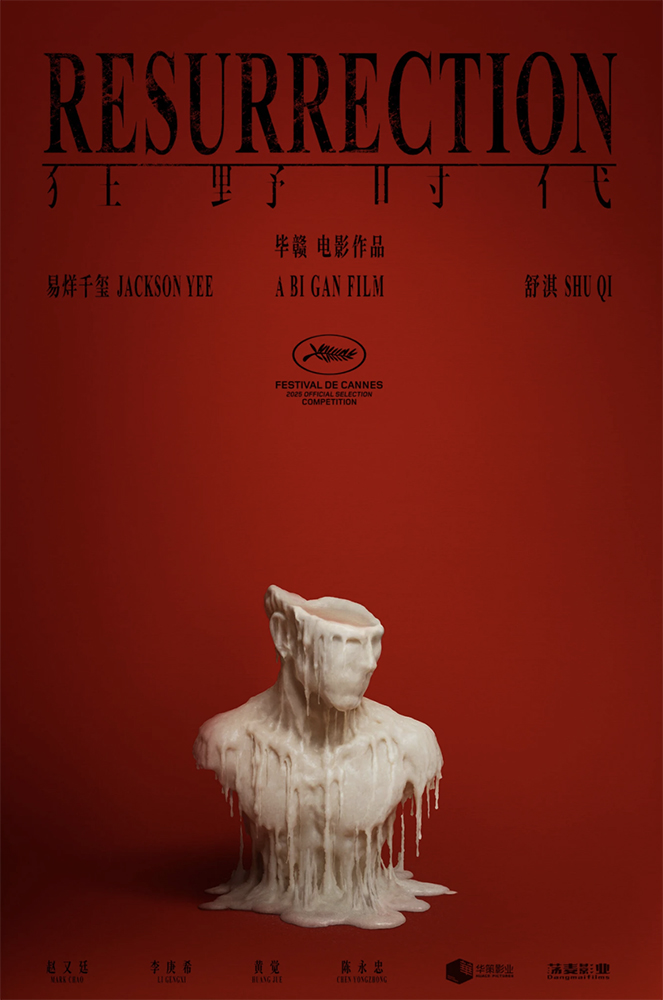

Bi Gan’s Resurrection is a visual juggernaut—equal parts baroque hallucination and cinematic monument, as if Everything Everywhere All At Once collided with Inception, filtered through Tarkovsky’s mirror and drenched in the hyper-reality of Wong Kar-wai’s color palette. A film of breathtaking ambition and almost terrifying precision, it unfolds like a pharaonic edifice of moving images: grand, sculptural, obsessive.

From the very first frame, it’s clear: this is a world built entirely out of cinema. Each element feels borrowed from the pantheon—Nosferatu’s hand, Dalí’s eye, Hitchcock’s zoom. Bi Gan doesn’t hide his references; he erects them like shrines. The camera glides through spaces that seem sacred, frozen in time, so perfectly composed you could extract stills and hang them in a gallery.

But what are we looking at? And more importantly: why?

A World Without Death, a Cinema Without Breath

The premise is thrilling: in a future where humans have conquered death, reverie is forbidden, and only a few clandestine dreamers resist. We follow 100 years of rebellion across interwoven narratives, each more labyrinthine than the last. The structure is dizzying. Time folds. Stories collapse. Memory is a glitch. It’s meant to disorient—and it succeeds.

Yet for all its ingenuity, Resurrection risks being cinema’s most beautiful mausoleum. The imagery is exquisite, yes, the craft undeniable. But there’s a lingering emptiness, a hollowness beneath the gilded surfaces. A dream constructed with such care that the dreamer, somewhere along the way, has vanished.

“If I lose my years, I might pass to the other side of the mirror.”

Where others use dreams to write, Bi Gan uses dreams to deconstruct. But in chasing aesthetic perfection, he loses touch with the messy, organic logic that makes dreams alive. The film becomes not surreal, but sterile. Not poetic, but mannered. A machine built to simulate transcendence.

The Dissonance of Mastery

There’s a philosophical core here, and it’s profound: immortality, stripped of mortality’s urgency, becomes a kind of hell. In a world without death, there is no risk. No sacrifice. No need for art. No need for poetry. No hunger for meaning. The soul atrophies.

This is the film’s great idea, and yet, paradoxically, it forgets its own lesson. For nearly three hours, Resurrection bathes us in immaculate, technically masterful imagery, with all the passion of a museum curator and none of the wild desperation of an artist confronting the void.

“What is the most sorrowful thing in this world?

All is but illusion.

What can we do alone and not in two?

Dream.”

And therein lies the contradiction: the film yearns for poetry, but silences it. It reveres cinema, but embalms it. The result is a dissonant symphony—grandiose, calculated, and ultimately inert. We are left not with the warmth of transformation, but with the cold beauty of a dream no one wakes from.

A Monument to Cinema—But to What End?

Resurrection is a remarkable technical achievement. A monumental fresque. Its ambition alone deserves recognition. But it is also a cautionary tale—of what happens when cinema forgets its beating heart in pursuit of its perfect face.

Bi Gan’s film asks: what remains when there’s nothing left to strive for? Perhaps the same can be asked of the film itself.